Malaria Impact Calculator

Enter Child Information

Impact Summary

Key Metrics

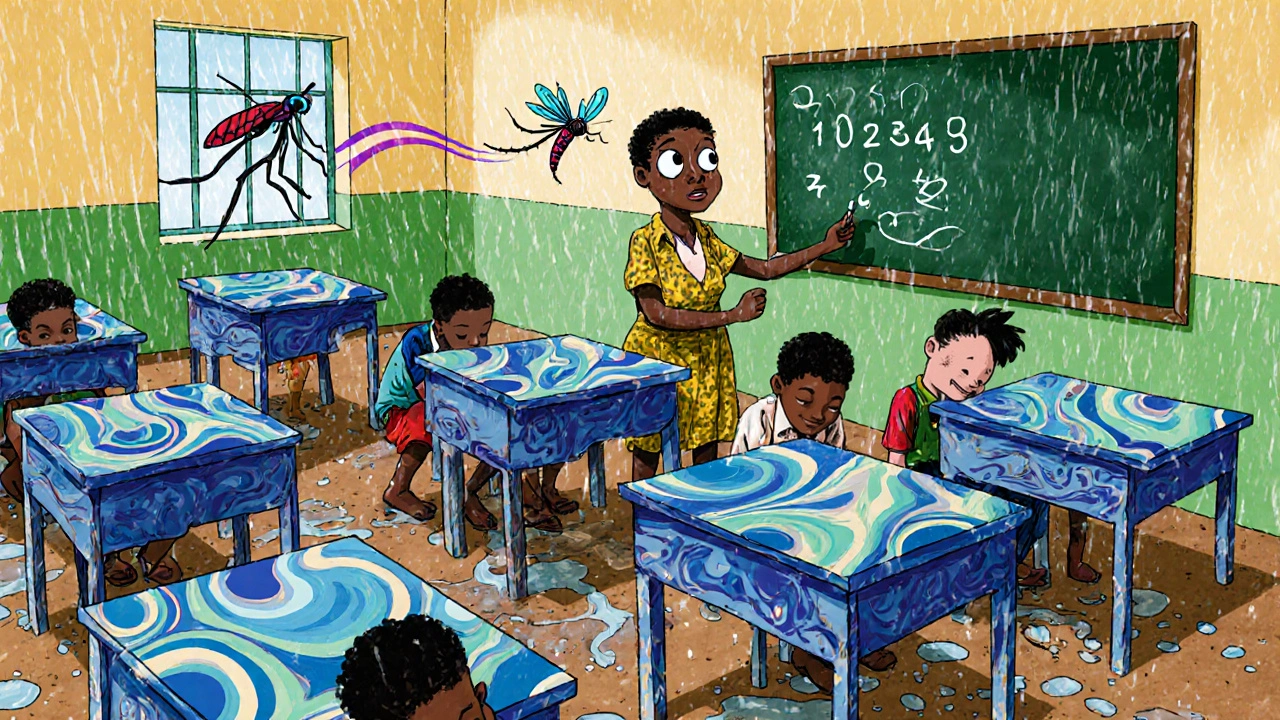

Malaria is a mosquito‑borne disease caused by Plasmodium parasites transmitted through the bite of an infected Anopheles mosquito. It remains a leading cause of illness and death in many low‑and‑middle‑income countries, especially among children under five.

Education is the process through which children acquire knowledge, skills, and attitudes that enable them to participate fully in society. When health problems like malaria disrupt schooling, the ripple effects on learning can last a lifetime.

Why Malaria Still Threatens Learning

Even though we have effective treatments, malaria still accounts for more than 200 million cases worldwide each year. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that sub‑Saharan Africa bears roughly 90% of the burden. In regions where schools are within walking distance of breeding sites, children are exposed daily.

Two health pathways make malaria especially damaging for learners:

- Acute illness: Fever, chills, and severe headaches force children to stay home for at least 3‑5 days, often longer if complications arise.

- Chronic effects: Repeated infections lead to anemia and cerebral involvement, both of which impair cognitive development.

Combining these pathways creates a perfect storm for school absenteeism and poorer academic outcomes.

From Illness to Missed Classes

Data from UNICEF’s 2024 school‑health survey show that children who missed a malaria episode missed an average of 7.2 school days per year-about 15% of the total school calendar in many African nations. In Kenya’s high‑risk counties, the absenteeism rate climbs to 23% during peak transmission months.

Beyond the raw numbers, the timing matters. Missing school during key learning periods-like the first half of the academic year-means falling behind in literacy and numeracy foundations that are hard to recover.

How Malaria Hits Cognitive Development

Repeated malaria infections often cause iron‑deficiency anemia. Iron is vital for oxygen transport to the brain; low levels reduce attention span, memory retention, and processing speed. A 2023 longitudinal study in Tanzania linked three or more malaria episodes before age five to a 12‑point drop in standardized math scores by eighth grade.

Severe cerebral malaria can cause lasting neurological damage. Even when children survive, subtle impairments in executive function-planning, problem‑solving, and impulse control-are common. These deficits translate directly into lower classroom participation and test performance.

Academic Performance Gaps

When we compare test scores of children in endemic areas with their peers in low‑risk zones, the gaps are stark:

| Subject | With frequent malaria | Without malaria |

|---|---|---|

| Reading | 68 | 78 |

| Mathematics | 62 | 75 |

| Science | 65 | 80 |

These gaps widen over time because children who miss school also miss remediation opportunities, creating a cumulative disadvantage.

Long‑Term Consequences Beyond the Classroom

Education is a strong predictor of future earnings. A World Bank analysis (2022) estimated that each additional year of schooling raises average lifetime earnings by 10%. If malaria cuts schooling by 0.3‑0.5 years on average, the economic loss per affected child can exceed $1,500 in today’s dollars-a significant amount in low‑income economies.

Gender amplifies the issue. Girls often bear the brunt of caregiving duties when a sibling falls ill, leading to even higher dropout rates. In Nigeria, 28% of girls in malaria‑high districts leave school before completing primary education, compared with 19% of boys.

What Works: Interventions That Protect Learning

Several evidence‑based strategies have proven effective at breaking the malaria‑education link:

- Insecticide‑treated nets (ITNs): Distributed through campaigns led by UNICEF, ITNs reduce malaria incidence by up to 50% in school‑age children.

- Intermittent preventive treatment for school‑aged children (IPT‑SC): A single dose of Artemisinin‑based Combination Therapy given every school term cuts infections by 35%.

- School‑based health education: Teaching kids how to avoid mosquito bites and recognize early symptoms leads to faster treatment seeking.

- On‑site rapid diagnostic testing: Allows teachers or health volunteers to confirm malaria quickly and start treatment, shortening sick days.

- Nutrition programs: Iron‑rich meals address anemia, improving both health and cognition.

When these measures are combined, some districts in Ghana have seen a 22% rise in attendance and a 7‑point gain in test scores within two years.

Policy Recommendations for Governments and NGOs

To sustain progress, stakeholders should focus on three policy pillars:

- Integrate health services into schools: Routine screening, treatment, and distribution of ITNs should become part of the school calendar.

- Secure financing for preventive tools: Allocate budget lines for bed nets, ACT drugs, and training of school health staff.

- Monitor and evaluate outcomes: Use school‑level data on attendance and test scores to gauge impact and adjust programs.

Cross‑sector collaboration-between ministries of health, education, and finance-ensures that interventions are not siloed but reinforce each other.

Key Takeaways

- Malaria directly reduces school attendance, with affected children missing an average of 7+ days per year.

- Repeated infections lead to anemia and cerebral damage, lowering cognitive performance and test scores.

- Girls and children from the poorest households face the steepest educational setbacks.

- ITNs, school‑based preventive treatment, and nutrition programs can shrink the attendance gap by up to a quarter.

- Policymakers need coordinated school‑health strategies to protect learning and future earnings.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does malaria cause anemia in children?

The malaria parasite destroys red blood cells during its life cycle. This loss, combined with the body’s reduced ability to produce new cells during infection, leads to iron‑deficiency anemia, which impairs oxygen delivery to the brain and muscles.

What age group benefits most from school‑based malaria interventions?

Children aged 5‑14, who are in primary and lower secondary school, show the biggest gains in attendance and test scores when given ITNs and IPT‑SC, because they spend most of their day at school and are highly exposed to mosquito bites during peak biting hours.

Are insecticide‑treated nets safe for school environments?

Yes. ITNs are made of polyester fabric coated with long‑lasting insecticide. They are safe for children and adults, and they remain effective for up to three years with proper care.

How can teachers identify a child who might have malaria?

Key signs include a sudden fever above 38°C, chills, headache, and fatigue. Training teachers to recognize these symptoms and refer the child for rapid testing can cut sick days dramatically.

What is the cost‑effectiveness of providing ITNs at schools?

A 2022 WHO analysis found that the cost per disability‑adjusted life year (DALY) averted is under $30 when nets are distributed through schools, making it one of the most affordable public‑health interventions.

Angela Koulouris

October 21, 2025 AT 14:51Seeing the data on missed school days makes me think of each child as a blank canvas. A single insecticide‑treated net can splash a splash of color onto that canvas, brightening the future. If we keep the brushstrokes steady, the picture improves for entire communities.

Harry Bhullar

October 21, 2025 AT 23:26Let me break this down step by step, because the interplay between malaria and learning is far from trivial. First, the acute febrile episodes force kids out of the classroom for anywhere between three to five days, sometimes longer if complications arise. Second, repeated infections bring chronic anemia, which starves the brain of oxygen and hampers cognitive processes like attention and memory. Third, cerebral malaria can cause subtle but lasting deficits in executive function, meaning planning and problem‑solving take a hit. All of these health setbacks translate directly into poorer test scores, as the longitudinal Tanzanian study you mentioned demonstrates. Moreover, absenteeism during the critical early school years compounds the problem because foundational literacy and numeracy skills are delayed. When you aggregate these effects across a whole cohort, the educational gap widens year after year, creating a feedback loop of disadvantage. On the bright side, interventions like insecticide‑treated nets and intermittent preventive treatment have shown measurable impacts. For instance, a single ITN distribution can cut incidence by up to 50 percent in school‑age children, which subsequently reduces the number of missed school days. Layering that with on‑site rapid diagnostic testing shortens the duration of illness even further. Nutrition programs that address iron deficiency can also offset the anemia‑related cognitive loss. Finally, coordination between health and education ministries ensures that these tools are not deployed in isolation but reinforce each other, maximizing the return on investment. In sum, the evidence points to a clear, actionable pathway: treat malaria as an educational issue as much as a health issue, and you’ll see gains on both fronts.

Dana Yonce

October 22, 2025 AT 08:36Great summary! 😊 This really shows why we can't ignore malaria in the classroom.

Lolita Gaela

October 22, 2025 AT 17:46The epidemiological burden outlined here underscores the need for integrated school‑health platforms. Deploying ITNs alongside IPT‑SC constitutes a synergistic vector‑control and chemoprophylaxis model, reducing entomological inoculation rates and parasite prevalence simultaneously. Moreover, iron supplementation addresses the hematological sequelae that impair neurocognitive development, as evidenced by the hemoglobin‑cognition correlation coefficients in recent meta‑analyses.

Giusto Madison

October 23, 2025 AT 02:56While Harry’s deep dive is thorough, let's cut to the chase: schools need a rapid‑response kit now. One dose of ACT every term, plus on‑site RDTs, can slash sick days dramatically. No excuse for waiting on bureaucratic red tape when kids are missing critical lessons.

eric smith

October 23, 2025 AT 12:06Oh, so you think handing out nets is the silver bullet? Please, that's the same old banana‑splitting argument. Without addressing vector breeding sites and socioeconomic determinants, you're just putting a band‑aid on a broken dam.

Erika Thonn

October 23, 2025 AT 21:16i think this is like a deep river of nothng where the kids walk accross and they cant see the dark side of the waterh nd they cant get school because of death

Ericka Suarez

October 24, 2025 AT 06:26This is the price of weakness!

Jake Hayes

October 24, 2025 AT 15:36Data doesn’t lie; the solution is obvious.

erica fenty

October 25, 2025 AT 00:46Indeed, the numbers are striking!; however, policy inertia often stalls progress; let’s push for actionable steps; data‑driven interventions, now!!!