When someone overdoses on more than one drug at once, it’s not just a bigger overdose-it’s a completely different kind of emergency. Mixing opioids with acetaminophen, or benzodiazepines with alcohol, doesn’t simply add up the dangers. It creates unpredictable, life-threatening interactions that standard protocols often don’t prepare you for. In 2019, opioids alone killed 120,000 people worldwide. But when those opioids are mixed with other drugs-like the acetaminophen in Vicodin or the benzodiazepines in Xanax-the risk of death jumps dramatically. And yet, many first responders and even some hospital staff still treat these cases as if they’re dealing with a single-drug overdose. That mistake can be fatal.

Why Multiple Drug Overdoses Are So Dangerous

Most people think of overdoses as one drug gone wrong. But in reality, nearly half of all fatal overdoses now involve multiple substances. The most common combinations? Opioids with acetaminophen, opioids with benzodiazepines, or alcohol mixed with any of these. Each drug in the mix doesn’t just add to the problem-it changes how the others behave in the body.

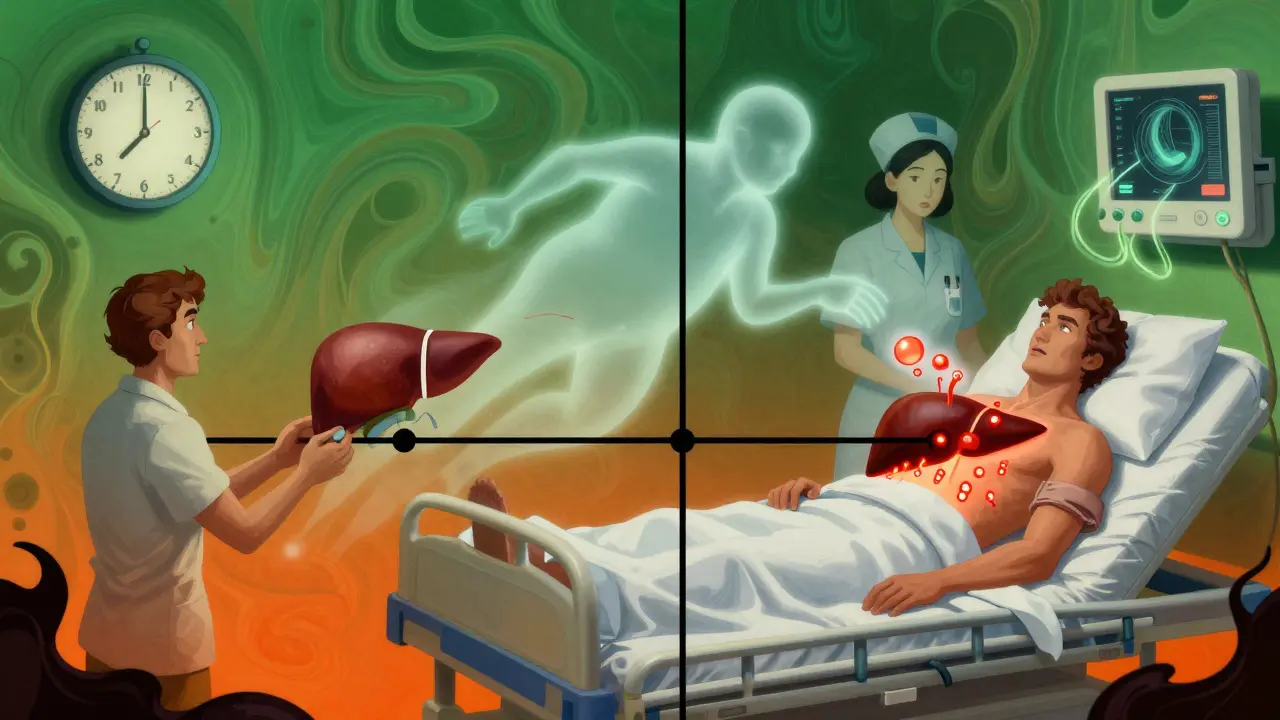

Take a prescription painkiller like Percocet. It contains oxycodone (an opioid) and acetaminophen (a common pain reliever). If someone takes too much, they’re not just at risk of breathing stopping-they’re also at risk of their liver failing. Naloxone can reverse the opioid part, but it does nothing for the acetaminophen. And that liver damage? It doesn’t show up right away. It can take 24 to 48 hours for symptoms to appear. By then, it might be too late.

Or consider mixing opioids with benzodiazepines. Both depress the central nervous system. Together, they can shut down breathing faster and deeper than either drug alone. Flumazenil can reverse benzodiazepines, but if the person is dependent on them, using flumazenil can trigger violent seizures. So you’re stuck: treat one drug and risk triggering another crisis.

This is why managing multiple drug overdoses isn’t about picking one antidote-it’s about running a coordinated medical response that handles all threats at once.

The Core Treatment Protocol: Naloxone, Acetylcysteine, and Timing

If you suspect a multiple drug overdose, your first move is the same as any opioid overdose: give naloxone. The SAMHSA Five Essential Steps are clear: assess, call for help, administer naloxone, support breathing, and monitor. But here’s where most people get it wrong-they stop after one dose.

Fentanyl and its analogs are 50 to 100 times stronger than heroin. One dose of naloxone might bring someone back, but if the fentanyl is still in their system, they can crash again in 30 to 90 minutes. That’s why you need to be ready to give a second-or even third-dose. And you can’t just walk away after they wake up. The WHO and SAMHSA both stress that naloxone wears off faster than most opioids. If you don’t get them to a hospital, they could die after seeming fine.

Now, if acetaminophen is involved, you need acetylcysteine. The JAMA Network Open 2023 guidelines say you should start it within 8 hours of ingestion for the best outcome. But here’s the catch: you don’t wait for blood tests. If someone took a pill that contains acetaminophen and overdosed, assume it’s toxic until proven otherwise. For adults over 100 kg, dosing is capped at 100 kg-no more, no less. Giving too much can cause side effects; giving too little won’t protect the liver.

And timing matters. Naloxone works in minutes. Acetylcysteine takes hours to build up in the bloodstream. So you might see someone breathe normally after naloxone-but their liver could be silently dying. That’s why monitoring for 24 hours is non-negotiable. Even if they seem fine, you need blood tests for liver enzymes (AST, ALT) and acetaminophen levels.

Special Cases: Tramadol, Repeated Ingestions, and Chronic Conditions

Not all opioids are the same. Tramadol is often mistaken for a "safe" opioid because it’s used for chronic pain. But it’s not just an opioid-it also affects serotonin. Overdosing on tramadol can cause seizures, serotonin syndrome, and respiratory failure. Naloxone works on tramadol, but because it has a 5- to 6-hour half-life, you often need a continuous IV drip, not just a single injection.

Then there’s repeated supratherapeutic ingestion-when someone takes a little too much acetaminophen every day for a week. It’s not a single overdose. It’s chronic toxicity. The JAMA guidelines say if acetaminophen levels are above 20 μg/mL or liver enzymes are elevated, give acetylcysteine. Don’t wait for symptoms. People with alcohol use disorder, malnutrition, or liver disease are at higher risk-even if they didn’t take a "massive" dose.

And don’t forget the other health problems. Someone with heart disease, kidney failure, or diabetes? Their body handles toxins differently. A drug that’s safe for a healthy person might be deadly for them. Hospital protocols now require a full medical history check before starting treatment. A simple question-"Do you take anything daily?"-can change the entire treatment plan.

What Hospitals Do That You Can’t (And Why You Still Need to Act Fast)

Once someone gets to the hospital, things get more complex. They’ll run blood tests, check for kidney and liver function, monitor oxygen levels, and possibly do a CT scan if there’s concern about brain swelling. If acetaminophen levels hit 900 μg/mL or higher, and the patient has acidosis or confusion, they’ll start hemodialysis. Yes-dialysis. Not just to clean the blood, but to keep acetylcysteine circulating at the right level while removing the poison.

They might give activated charcoal-especially if the overdose happened within the last 4 hours. But charcoal isn’t magic. It doesn’t work on alcohol, opioids, or benzodiazepines. It only binds certain drugs in the gut. And if they give it, the patient needs to drink water. Charcoal can cause serious constipation. It can also mess with other meds-like birth control pills. So if they’re on the pill, they need backup contraception for the next month.

None of this happens without time. And that’s why your actions in the first 10 minutes matter more than anything else.

What First Responders and Bystanders Must Do

You don’t need to be a doctor to save a life in a multiple drug overdose. But you do need to know what to do-and what not to do.

- Don’t wait. If someone is unresponsive, not breathing, or has blue lips, act now. Don’t wait to see if they "wake up on their own."

- Give naloxone immediately. Even if you’re not sure opioids are involved. It won’t hurt if they’re not. It could save them if they are.

- Keep giving breaths. If they’re not breathing, start rescue breathing. Naloxone takes 2 to 5 minutes to work. Your breaths keep their brain alive until it kicks in.

- Give more naloxone if needed. If they don’t respond in 3 minutes, give another dose. Fentanyl overdoses often need two or three.

- Stay with them. Even if they wake up, don’t let them go home. They could crash again. Call emergency services and don’t leave until help arrives.

And if you’re in a community where opioid overdoses are common-like near shelters, prisons, or in areas with high prescription use-keep naloxone on hand. The WHO says programs that give naloxone to people who use drugs, their friends, and family members have cut overdose deaths by up to 50% in some areas.

The Bigger Picture: Overdose Isn’t Just a Medical Issue

Treating a multiple drug overdose is only half the battle. The other half is what happens after.

Studies show that people who survive an overdose are 100 times more likely to die in the next year. Why? Because the system often fails them after the ER. They get discharged without follow-up. No counseling. No medication-assisted treatment like methadone or buprenorphine. No connection to support services.

That’s why the best outcomes happen when emergency care leads directly to long-term care. The American Addiction Centers stress that every overdose survivor should be referred to a primary care provider within 72 hours. Not just for liver checks-but to talk about substance use, mental health, and recovery.

Public health programs that combine naloxone distribution with access to treatment are working. In New Zealand, where I’m based, pilot programs in Wellington have started training peer support workers to hand out naloxone kits and connect people to counselors the same day. Early results show a 30% drop in repeat overdoses in those groups.

Multiple drug overdoses aren’t just medical emergencies. They’re signs of a broken system. And fixing them means more than just having the right antidotes. It means having the will to follow through-on the call, in the hospital, and long after the patient walks out the door.

What to Do If You’re Worried About Someone

If you’re concerned about a loved one taking too many pills, don’t wait for a crisis. Talk to them. Ask if they’ve ever felt dizzy, nauseous, or confused after taking their meds. Check if they’re mixing prescriptions with alcohol or sleep aids. Look for empty pill bottles or hidden stashes.

And if you’re not sure what’s in their medicine cabinet? Look up the names on a reliable site like MedlinePlus. Many combination pills have acetaminophen in them-and people don’t realize it.

Keep naloxone in your home if someone you care about uses opioids, even if they’re prescribed. It’s not about judging. It’s about being ready.

Annette Robinson

January 8, 2026 AT 22:08I’ve seen too many people dismissed after a single dose of naloxone. I work in ER triage, and the moment someone wakes up, they’re told, ‘You’re fine, go home.’ But the liver damage? The delayed respiratory arrest? No one checks. We need mandatory 24-hour observation for any combo overdose-no exceptions. This isn’t just protocol, it’s basic human care.

Luke Crump

January 9, 2026 AT 07:00Let’s be real-this whole system is a theater of cruelty. We give people naloxone like it’s a magic bullet, then toss them back into the same poverty, trauma, and prescription mills that got them there in the first place. The real overdose isn’t the drugs-it’s the society that keeps handing out pills like candy and then acts shocked when people die. We’re not treating addiction. We’re treating symptoms while the disease eats the whole damn body.

Manish Kumar

January 11, 2026 AT 03:15Interesting how we focus so much on the pharmacology of overdose but ignore the existential void that drives people to mix substances in the first place. The opioid crisis isn’t a medical anomaly-it’s a cultural collapse. People aren’t just overdosing on drugs; they’re overdosing on loneliness, on broken families, on the illusion that productivity equals worth. Acetylcysteine saves livers, but it doesn’t heal the silence after a parent dies alone in a motel room with empty pill bottles and a phone that never rang. We treat the body while the soul screams into the void.

Prakash Sharma

January 11, 2026 AT 18:07Why are we letting Western medicine dictate global health norms? In India, we’ve managed chronic pain for centuries with Ayurveda and community care. Now we’re copying your naloxone culture like it’s gospel. But you don’t fix a broken society by handing out antidotes-you fix it by rebuilding dignity. Stop treating addiction like a Western problem. This isn’t about chemistry-it’s about control. And you’re losing.

Kristina Felixita

January 13, 2026 AT 04:41OMG, this post is so important!! I had no idea acetaminophen was in so many painkillers!! I thought it was just Tylenol?? Like, I literally gave my cousin naloxone last year after she passed out, and we didn’t even know she’d taken a Vicodin-she thought it was just "a little stronger" than her usual meds??!! We need WAY more public education!! Like, billboards, TikTok videos, school assemblies-this stuff is LITERALLY killing people and no one talks about it!!

Joanna Brancewicz

January 13, 2026 AT 05:24Naloxone is necessary but insufficient. Acetylcysteine must be initiated empirically in suspected APAP co-ingestion. Delay = mortality. Monitor AST/ALT, INR, lactate. Discharge only after 24h with follow-up scheduled. No exceptions.

Ken Porter

January 14, 2026 AT 03:00Another liberal panic piece. You want to save lives? Stop legalizing weed and fentanyl analogs. Stop giving out naloxone like candy to junkies who OD on purpose to get free housing. This isn’t a medical crisis-it’s a moral one. Stop enabling. Start holding people accountable.

swati Thounaojam

January 14, 2026 AT 08:39i just wanted to say thank you for writing this. my sister died last year from mixing xanax and painkillers. no one told us the liver thing could happen later. we thought she was safe after naloxone. we didn’t know. please share this. so many don’t know.

Dave Old-Wolf

January 14, 2026 AT 11:01Wait, so if someone takes tramadol and it’s still in their system for 6 hours, and naloxone only lasts 30-90 minutes… does that mean you’d need to keep giving naloxone over and over? Or is there a better way? I’m trying to understand-because if I had to do this in real life, I’d be terrified I’d miss something. Also, what about people who don’t have access to hospitals? Like in rural areas? How do you even begin to handle this?